MacroMania

Believe those who are seeking the truth. Doubt those who find it. Andre Gide

Monday, March 17, 2025

The End

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

Blanchard on Trumponomics

How will Trumponomics work out? This is a question that many people are asking, including Olivier Blanchard (see here). Blanchard focusses on three broad policy characteristics of Trumponomics: tariffs, tax cuts, and mass deportations of illegal immigrants. His analysis is based on "textbook macroeconomic principles." His conclusion is that the president-elect will be disappointed with the results, but that the outcome will not be the catastrophe that many are predicting. This may very well be the case. But the purpose of this piece is not to question Blanchard's prediction. What I want to do instead is evaluate the reasoning he applies to each policy (a reasoning based on "textbook macroeconomic principles."

Tariffs.

Blanchard predicts that a broad-based tariff policy (if enacted) will cause a decline in U.S. imports and an increase in tariff revenue; at least, in the short run. U.S. demand will shift from foreign to domestic goods and services. Since the U.S. economy is close to full employment, the increase in demand for domestically produced goods and services will manifest itself as inflation. This inflationary burst will likely lead the Fed to raise its policy rate. Higher interest rates will strengthen the U.S. dollar, discouraging U.S. exports. Retatiatory tariffs would reduce the foreign demand for U.S. exports even more. Summary: higher interest rates, higher inflation, little change in the trade deficit, unhappy exporters.

This seems plausible. A broad-based tariff is likely to increase the cost-of-living; at least, in the short run. The rate of change in the cost-of-living (the inflation rate), however, is likely only to jump up temporarily; see, for example, how increases in the Japanese VAT correlate with inflation:

Would the Fed necessarily raise its policy rate against a temporary burst of inflation that was not demand-driven? A case could be made that it should not. Given the recent experience, however, it wouldn't be unreasonable to expect policy to tighten. Blanchard believes that this will cause the USD to appreciate, discouraging U.S. exports. But why wouldn't these discouraged exporters then not try to redirect their sales to the domestic market? If they did, this should put downward pressure on domestically produced goods and services, and downward pressure on inflation. Of course, all sorts of things may happen instead. For example, reduced profit margins may lead to layoffs. I'm not sure how many of these effects Blanchard's simple model takes into account.Immigration

It is estimated that there are approximately 10M illegal immigrants in the U.S., representing about 5% of the workforce. Blanchard believes that deporting immigrants (say, 1M/year) will lead to an increase in the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio (a measure of the tightness of the labor market) which will, in turn, lead to persistently higher inflationary pressure, leading the Fed to raise its policy rate. Again, higher inflation and interest rates is not what the new administration is looking for. However distasteful one finds the concept of mass deportations, this is not a new phenomenon in the U.S.; see (source): What is remarkable about the fact above is how almost nobody talks about it. Why the sudden concern on how the policy might affect inflation and interest rates? Blanchard believes that inflationary pressure and employer resentment will mean the deportations will not happen on a mass scale. While this may turn out to be the case, the rationale Blanchard bases his conclusion is not supported in the data.Tax cuts

I've expressed concerns over the projected path of fiscal policy for a while now; see here. I've also written on how I believe we've switched from a deflationary-pressure regime to an inflationary-pressure regime; see here. I do not, however, see these concerns as being specific to Trumponomics--a new Harris-Walz administration would not likely have had much an effect on the tectonic forces determining these regimes.One factor I've not emphasized in my discussions is the prospect of a sustained boom in U.S. productivity. Roger Farmer suggests (see here) that regulatory reforms in the oil and gas sector may indeed unleash a productivity boom. The resulting boom in economic activity would make the growing supply of U.S. Treasury securities more "sustainable" (in the sense that USTs would be more willingly held at lower yields and lower rates of inflation). It is interesting to note that "r less than g" continues to be a property of the U.S. economy, though barely:

I suppose the question boils down to "Whither r v g?"Friday, February 9, 2024

Does high-interest policy constitute fiscal stimulus?

One idea floating around out there is that high interest rate policy constitutes of a form of fiscal stimulus. Here's Stephanie Kelton expressing the idea:

And here's my friend Sam Levey suggesting the same thing: For ears attuned to conventional wisdom, this idea sounds bizarre and counterintuitive. But I think there's a way to reconcile these different views. The first step toward reconciliation is to understand the difference between increasing the interest rate and keeping it elevated. That is, we need to make a distinction between change and level.I think *changes* in the policy rate seem to work the way conventional wisdom dictates (i.e., lowering aggregate demand through a variety of channels). One important channel works through the wealth effect (e.g.):

Once the policy rate remains stable and the transition dynamics work their way through ("long and variable lags"), the higher policy no longer appears contractionary. In fact, high interest rate policy may very well be expansionary, as Stephanie and Sam suggest. How might this work?In the class of economic models I work with (e.g., see here), monetary (interest rate) policy and fiscal (tax & spend) policy are inextricably linked through a consolidated government budget constraint. A *change* in the policy rate has all the textbook effects of monetary policy--but only in the "short-run." So, for example, while an *increase* in the interest rate puts downward pressure on the price-level, the disinflationary force is transitory (the P-level remains permanently lower if the policy rate remains permanently higher, but the rate of change of the P-level in the long-run remains unchanged).

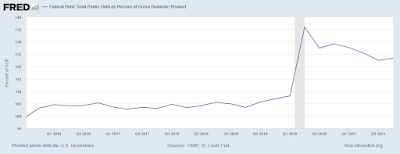

At least, this is what is predicted to happen if the fiscal policy framework is "Ricardian." A Ricardian fiscal policy is one in which the path of the primary deficit/surplus adjusts over time to anchor a given debt-to-GDP ratio. A Ricardian fiscal regime is often just assumed in economic models. This assumption seems hard to reconcile with the fact that Congress does not appear to implement offsets to Fed policy. At least, it does not appear to do so immediately. It is, however, possible that the offsets (higher taxes, lower spending) are postponed to the future (perhaps after our representatives become alarmed by posts like Marc Goldwein above).

But there is another possibility. It could be that the fiscal regime is "Non-Ricardian." A Non-Ricardian fiscal policy does not anchor fiscal policy in the way a Ricardian regime does--it does not offset higher interest expense (and higher interest income for bond holders) with higher future taxes and/or lower future spending. To finance the added interest expense, it just lets the Treasury issue nominal Treasury securities at a faster pace. If the Fed keeps its policy rate steady (at its higher level), then this additional flow of private sector wealth is likely to manifest itself as stimulus (higher inflation, if the economy is at full employment). Is this where we're at today?

Of course, the Fed is likely to react to the situation described above by *increasing* its policy rate again. But if fiscal policy is Non-Ricardian, the disinflationary pressure induced by the rate change will eventually dissipate. Indeed, it will result in an even higher rate of inflation in the long-run. This is related to the "Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic" argument put forth by Sargent and Wallace over 40 years ago; see here: Is it Time for Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic? And in case you believe this scenario is only hypothetical, consider this paper on the Brazilian hyperinflation: Tight Money Paradox on the Loose: A Fiscalist Hyperinflation. (Note: this is not to suggest that the U.S. is Brazil.)As always, please feel free to share your thoughts below.

DAMonday, July 17, 2023

Constrained efficient inflation

I haven't had time to do much blogging lately. But I have been studying the recent burst of inflation and thinking of how to interpret what we're experiencing. As is my way, I decided to write down a little model (a dynamic general equilibrium model) to help organize my thinking on this question. Below, I summarize the interpretation stemming from the model (available on request). Because it's a model, it does not capture everything that one might think isimportant. But I think it certainly captures some of the main forces operating on the U.S. economy over the 2020-2022 time period. And if so, then it offers a different take on how to interpret the recent episode of (relatively) high and (hopefully) transitory inflation. I look forward to any feedback. DA

Introduction

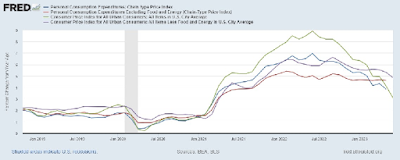

In February 2020, the month before the full effects of the pandemic were felt in the United States, PCE and CPI measures of inflation were running between 1.7% and 2.4%, consistent with the Federal Reserve's official 2% target inflation rate. From March 2020 to February 2021, these measures of inflation declined significantly, with most measures falling below 1% in May 2020, before recovering to somewhere near 1.5% by February 2021. In March 2021, measures of inflation began to rise sharply and significantly. By February 2020, the month prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, PCE and CPI inflation rates rose to between 5.4% to 8.0%, with core PCE peaking in that month. Other measures of inflation peaked in the summer of 2022. Inflation has been declining slowly and steadily since then. Most outlooks have inflation declining to between 2% and 3% by the end of 2024.

If inflation continues along its projected path to settle in at or even somewhat above 2%, then the recent inflation dynamic will be hump-shaped, beginning in 2021, peaking in 2022, and falling significantly in 2023; see Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1 |

How should we interpret the hump-shaped inflation dynamic in Figure 1? The answer to this question is critically important because an evaluation of monetary and fiscal policy over this episode requires a proper interpretation of the phenomenon being studied. More than one interpretation is possible, of course. But any useful interpretation will have to rely on theory at some level. The goal of this paper is to develop a dynamic general equilibrium model that can explain the qualitative properties of data in an empirically plausible manner and be used to assess the monetary and fiscal policies employed since March 2020.

An overview of the argument

Views on the causes and nature of the "COVID-19 inflation" vary considerably. There is no doubt an element of truth to many of these views and my interpretation below relies on more than one causal factor.

Beginning in March 2020, there were the supply disruptions induced by the pandemic. Some sectors of the economy, like leisure and hospitality, were virtually shut down in an attempt to "flatten the curve." Individuals stopped patronizing establishments delivering in-person services. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio fell from 80% to 70% from February to April in 2020 and did not recover its initial level for another two years. Severe disruptions in the global supply chain led to shortages of goods at final destinations. At the time these COVID-19 related shocks had more or less dissipated, additional disruptions emerged with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 along with growing Sino-American tensions.

These "supply side" shocks were real and significant. It is not entirely clear, however, how they might be used to understand the inflation dynamic in Figure 1. The intensity of the "supply side" shock likely peaked in 2020, a year in which inflation declined. And the Russia-Ukraine war shock appeared in 2022, after the sharp rise in inflation in 2021. Of course, these observations do not mean that supply disruptions had no effect on the inflation dynamic. But they do suggest that other forces were likely at work.

Other important forces were surely at work on the "demand side" of the economy. Exactly what these forces were and how they should be modeled remains an open question. Guerrieri, Lorenzoni, Straub, and Werning (2022) demonstrate how a negative sectoral supply shock in an incomplete markets setting can endogenously result in "deficient demand" (a decline in actual output in excess of the decline in potential output). Although their paper does not focus on inflation dynamics, the mechanism they identify is presumably disinflationary; at least, on impact.

Another way in which demand can be affected is through expectations. Developed economies devote significant amounts of time and resources to activities broadly classified as investments, including business fixed investment, residential investment, human capital accumulation, and job recruiting. The contemporaneous demand for goods and services devoted to investment (broadly-defined) surely depends on its expected rate of return. Indeed, there is considerable evidence suggesting that this is the case; see Liao and Chen (2023) and the references cited within. Whether these expectations are driven by news over economic fundamentals (e.g., Beaudry and Portier, 2006) or by purely psychological factors (e.g., Keynesian "animal spirits") matters little for positive analysis. Depressed expectations over the return to investment will depress investment demand whether expectations are formed rationally or not. The manner in which expectations are formed does, however, have implications for monetary and fiscal policy.

The analysis below assumes a large "negative sentiment shock" in 2020, consistent with the fear and uncertainty associated with the unfolding pandemic and the dramatic measures taken to shut down parts of the economy. When the outlook on investment returns darkens, investors typically seek safe havens. During the financial crisis of 2008-09, U.S. Treasury securities served as a "flight to safety" asset. The result was plummting bond yields. To the extent that interest rates do not (or cannot) move lower, the demand for safety expresses itself as a decline in capital spending and the price-level. That is, a negative sentiment shock is disinflationary; at least, on impact. Below, I assume that this negative sentiment shock largely reversed itself in 2021, consistent with the appearance and widespread use of COVID-19 vaccines in that year.

Now, imagine for the moment, that monetary and fiscal policy remained roughly unchanged from 2019 to today. That is, imagine that the Fed did not lower its policy rate in March 2020 and that the large discretionary fiscal programs (primarily the CARES Act of 2020 and the American Rescue Plan of 2021) had not been implemented.

Assume that the negative sentiment shock was significantly more powerful than the negative supply shock in 2020, in line with Guerrieri, Lorenzoni, Straub, and Werning (2022). Assume that these two shocks are largely reversed in 2021. Then the supply-demand framework sketched above suggests a large disinflationary impulse and recession in 2020, followed by an equally large inflationary impulse and economic recovery in 2021. Depending on the nature of adjustment costs, employment and inflation should have more or less returned to their pre-pandemic levels by 2022 or shortly thereafter. To a first approximation, this is essentially what happened. However, actual inflation turned out to be much higher and more persistent than can be rationalized by these shocks alone. What is missing?

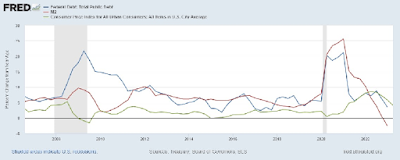

What is missing, of course, are the monetary and fiscal policy responses implemented at the start of the crisis. In March 2020, the Fed lowered its policy rate from 150bp to essentially zero where it remained until March 2022. The anticipated monetary tightening began in late 2021 (see the 2-year rate in Figure 2). From March to December of 2022, the federal funds rate rose by over four hundred basis points.

|

| Figure 2 |

From 2020 to 2021, the U.S. Congress passed a number of bills described as delivering "stimulus and relief." The two largest bills were the CARES Act, passed in March of 2020, and the American Rescue Plan (ARP), passed in March 2021. In broad terms, these spending packages had the following properties. First, the consisted largely of monetary transfers targeting the bottom half of the income distribution as well as distressed businesses. Second, the spending packages were large--around $2 trillion each--over ten percent of GDP in both 2020 and 2021. Third, the spending packages were not offset by spending reductions in other areas. Nor were surtaxes levied to finance the programs. The programs were financed with net new issuances of nominal securities purchased by the banking sector. That is, the transfers essentially took the form of "helicopter drops" of money; see Figure 3.

|

| Figure 3 |

The ultra loose monetary and fiscal policies over 2020-21 exerted strong inflationary pressures. In 2022, the Russian-Ukraine war contributed to headline inflation. The output loss in 2020 contributed to inflationary pressure. The reversal in business sentiment in 2021 contributed to inflationary pressure.

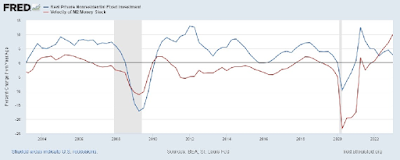

The inflationary pressures cited above were offset by strong deflationary pressures in 2020 and 2022. In 2020, there was a strong negative demand shock, resulting in a strong decline in investment with an accompanying movement in the demand for money (the inverse of money velocity); see Figure 4.

|

| Figure 4 |

As business sentiment reversed in 2021, the demand for money (safe assets, in general) declined. This turn of events occurred just as the ARP kicked in. Together, these two events generated a strong inflationary impulse in 2021. This impulse was counteracted in 2022 by strongly contractionary monetary and fiscal policies (a sharp rise in the policy interest rate in 2022 and the expiration of the ARP by the end of 2021).

The account given above is based on a model that I formalize below. Note that the account is purely qualitative in nature. This is because my model is designed only to flesh out the qualitative effects of a variety of economic forces that seem plausibly important (I am working on a quantitative version of the model with a coauthor). Formalizing the argument above through a simple dynamic general equilibrium model has two benefits. First, it will force me to be explicit about the assumptions I am making to render the verbal interpretation above logically coherent. Second, it will allow me to evaluate monetary and fiscal policies employed in the 2020-22 period. The model can also be used to perform counterf actuals.

Policy assessment

The model suggests the following assessment.

1. Cutting the policy rate in March 2020 was appropriate only to the extent that there were forces driving a declining output below potential. A strong deflationary pressure is not sufficient to identify an "output gap," because rationally-pessimistic forecasts are deflationary. One would have to make the case that investors became overly-pessimistic. Or that sectoral shocks somehow led to deficient demand (Guerrieri, et. al., 2022). These are difficult arguments to make because "potential" is unobservable and prior to the arrival of the vaccines, a gloomy sentiment did not seem irrational.

2. The fiscal transfers associated with the 2020 CARES Act were desirable. The policy mostly redistributed purchasing power (at a time when total output was declining) from high to low-income persons (the latter group being disproportionately affected by the shutdowns). Without the CARES Act, the economy would have likely experienced a significant deflation (benefiting those with wealth in the form of money/bonds). Hence, the desired redistribution was financed through an inflation tax. A temporary income or consumption tax might have been used instead. In this sense, inflation was at least in part an efficient tax (or constrained efficient, better ways of financing the desired transfers were available).

3. A case could be made that the 2021 ARP was desirable ex ante. A case could be made that it was undesirable ex post. Either way, the model suggests that the ARP was implemented at precisely the time investor sentiment had returned to normal. Essentially, 2021 saw a large increase in the supply of money and a large decrease in the demand for real money balances. Both effects served to drive inflation higher.

4. Strong disinflationary policies were enacted at the beginning of 2022. First, fiscal policy became highly contractionary (by ceasing the ARP). Second, the Fed began to raise its policy rate aggressively. These disinflationary policies were partially offset by the inflationary consequences of growing geopolitical tensions.

My own assessment of monetary and fiscal policy over this period of time (based in part on my model) is as follows. First, the Fed should not have lowered its policy rate in March 2020 (its emergency lending programs worked as needed). Conditional on having lowered the policy rate (forgivable, in light of the weak inflation numbers), the Fed should have begun tightening sometime in 2021 (consistent with the recommendations of those economists who favor NGDP targeting). Second, despite all its warts, the CARES Act was essential and did what it needed to do. Third, desirability of the ARP is better weighed in political, rather than economic, terms. It was a redistribution policy. It was financed through an inflation tax. It might have been financed in some less-inflationary way. But a tax in some form would have been unavoidable.

The policies and programs put in place by our elected representatives to meet the economic challenges inflicted on us by the pandemic were designed to redistribute purchasing power. If those policies were widely viewed as desirable, then it seems strange to blame inflation (or some other tax) for inflicting economic hardship. Inflation was mainly a symptom of the solution to a problem inflicted on humanity by nature. This is the sense in which one can describe the recent inflationary episode as "constrained efficient inflation."

PS. If the hump-shaped inflation pattern continues to play out, it will be judged by economic historians as a "transitory" inflation. There is nothing in the model which suggests that a recession is necessary for the transitory part. A helicopter drop of money creates a transitory inflation. This is textbook economics.

Saturday, March 18, 2023

There's No Free Lunch or: How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Not Hate Inflation

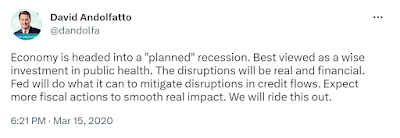

Remember when the Fed's most pressing policy concern was missing their 2% inflation target from below for most of the decade following the financial crisis of 2008-09? The concern never failed to puzzle me in all my time at the St. Louis Fed. I once let out how I really felt:

Well, inflation returned. But not exactly for the reasons I was expecting. What happened?

Shocks

What happened was COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. These two shocks were large, disruptive, and persistent. A great many people died. Large parts of the economy were shut down with the hope of slowing the spread of the virus so as not to overwhelm our limited ICU capacity. The leisure and hospitality sector was crushed, and other sectors as well. There was a massive (and highly unusual) reallocation of production and consumption away from services to goods--a phenomenon that has not fully reversed to this day. We learned about the delicate and interconnected nature of global supply chains. People modified their behavior in dramatic ways. Work-from-home seems here to stay. And then, of course, as if a global pandemic was not enough, Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, leading to the usual sickening consequences of war: death, destruction, and displacement--as well as energy disruptions and food shortages that reverberated across the global economy.

This is not, of course, the only thing that happened. We also had policy responses.

Policy: What was needed

I want to limit attention to economic policy here (health policy is another matter). The COVID-19 shock disrupted some sectors of the economy more than others. Some sectors, like leisure and hospitality were virtually shut down. But in many other parts of the economy, people were able to work from home. Since not many people purchased pandemic-insurance, a large number of Americans were in for a whole lot of economic hurt. Most of those adversely affected were in the bottom half of the income distribution. What could and should have been done?

I should like to think that most Americans would have been in favor of a social insurance program that supported those most in need; i.e., targeted transfers for as long as the pandemic remained disruptive. Most people would have recognized that this is the right thing to do. And even those few who seemingly do not care much for their fellow Americans might have recognized how redistribution would have been desirable, perhaps even necessary, to maintain social cohesion. We should not have wanted a replay of what happened in the last crisis, where the financial sector was bailed out while American many households were largely left flailing in the foreclosure winds that blew in the aftermath of 2008-09.

How might such a program be financed? A consumption tax would have been one way. Imagine a "transitory" 5% federal sales tax to fund a targeted transfer program. The program parameters could, in principle, be calibrated in a manner that requires little or no adjustment in the deficit. Ideally, such an emergency program would have already been put in place. (As far as I know, there is still no such plan in place--a significant policy failure, in my view.)

How might things have played out with such a policy, given the sequence of shocks that unfolded? To a first approximation, my guess is "probably not much different." With the balanced-budget policy described above, inflation would have almost surely been lower. Imagine shaving 300-500bp off the "inflation hump" we've experienced so far:

We would almost surely still have had some inflation stemming from supply disruptions and energy

costs (associated with the war). But inflation would have been less pronounced. Naturally, rather than complaining about high inflation, people would instead have

been complaining about high consumption taxes. ("They told us they'd be

transitory!") There's no such thing as a free lunch.

Under this higher-tax/lower-deficit policy, most Americans would have felt worse off relative to 2019. The blame for this feeling, however, properly lies with the shocks and not the policy response. Yes, work-from-home types would not have received transfers and they would have been paying more for goods and services. This is the nature of redistribution, which I believe most people would have supported.

Policy: What we got

To a large extent--and all things considered--we pretty much got what was needed: a set of redistributive policies with transfers targeted (mostly) to the bottom half of the income distribution (yes, yes, we can talk at length about how things could have been done better). Except that there was no surtax to fund the transfers. Our representatives in Congress chose to deficit-finance the programs. The resulting large quantity of treasury paper had to be absorbed by the private sector at a time supply was constrained and interest rates were not permitted to rise (I'll get to monetary policy in a moment). How does one not expect some additional inflation in this case? So, instead of a "transitory" consumption tax, we got a "transitory" inflation tax. There's no free lunch.

By the way, by "transitory" I mean to say that inflation is expected to revert to target, instead of remaining elevated or even increasing. In the fall of 2020, I expected a "temporary" inflation (see here) because I thought the supply disruptions and CARES Act were not permanent. Inflation turned out to be higher and more persistent than I expected. But the supply disruptions have largely alleviated and the ARP expired at the end of 2021 (though the RUS-UKR war continues). Up until recently, I remained optimistic that--absent further shocks and with responsible fiscal policy--inflation would make its way back down to target in 3-5 years without a recession. I'm not as optimistic today, but let me return to this below.

What about monetary policy? Well, I was very pleased with the way the Fed calmed financial markets in March 2020, as I expected it would.

Well done, Fed. But what about monetary (interest rate) policy?

Well, to be honest, monetary policy seemed a bit bonkers. Lowering the policy rate in response to recession engineered by a manufactured shutdown did not make much sense to me. My view was more in line with Michael Woodford's, as expressed here in his 2020 Jean Monnet lecture. What was needed was insurance, not stimulus. And this insurance needs to be delivered through fiscal policy.

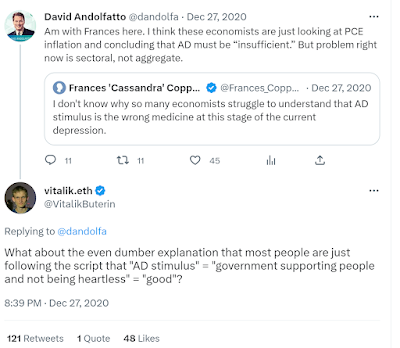

My own view is that many economists could not resist interpreting the severe decline in output as reflecting a conventional "output gap." To be fair, there may very well have been a decline in aggregate demand in the first half of 2020. The economic outlook at the time was very uncertain, which likely increased the desire for precautionary savings. Remember, monthly inflation rates for March, April and May of 2020 were negative. The monthly inflation rate only became positive in June 2020 (5.4% annualized rate), though it remained fairly subdued for most of 2020.

Heading into 2020, the Fed's policy rate was around 1.6%. Was it really necessary to lower it any further? Especially in light of the fiscal transfers taking place throughout 2020? But apparently, in the minds of some, perhaps even most, the economy needed "stimulating."

In any case, it seems clear now, in retrospect at least, that the cut should probably not have happened or, conditional on happening, should have been quickly reversed once the financial panic had subsided. The main effect of interest rate policy according to many was an undesirable asset-price boom (stocks, bonds, and real estate). The increase in private sector wealth coming from higher asset valuations surely added some fuel to the inflationary fire.

We can now see how that Fed-induced wealth effect is being undone. The rapidity of the rise in the Fed's policy rate is wreaking havoc on wealth portfolios. This is not a huge concern to the extent the policy is just reversing an undesirable asset-price inflation. But to the extent that these assets sit on bank balance sheets, to the extent these positions are not hedged against duration risk, to the extent that depositors are skittish, and to the extent that capital buffers are running low, then the banking system--or at least parts of it--are subject to runs. We are seeing this play out now in the United States.

Where are we heading?Thursday, April 7, 2022

What economic model produces the Fed's inflation forecast?

John Cochrane's blog has always been a favorite of mine. It's provocative. It's entertaining. And it invariably leads me to reflect on a variety of notions I have floating around in my head.

In his latest piece, he asks an interesting question: How does the Fed come up with its inflation forecast? What sort of model might be embedded in the minds of FOMC members? I like the question and the thought experiment. My comments below should not be construed as criticism. Think of them more as thoughts that come to mind in a conversation. (It's more fun to do this in public than in private.)

John begins with the observation that while the Fed evidently expects inflation to decline as the Fed's policy rate is increased, at no point in the transition dynamic back to 2% inflation is the real rate of interest very high. To quote John (italics in original): the Fed believes inflation will almost entirely disappear all on its own, without the need for any period of high real interest rates. Of course, this is in sharp contrast with the Volcker disinflation, an episode that demonstrated, in the minds of many, how a persistently high real rate of interest was needed to make inflation go down (some push back in this paper here).

John believes that the current inflation was generated in large part by a big fiscal shock in the form of a money transfer (an increased in USTs unsupported by the prospect of higher future taxes). I'm inclined to agree with this view, though surely there other factors playing a role (see here). John asks how this type of shock can be expected to generate a transitory inflation with the real interest rate kept (say) negative throughout the entire transition dynamic. Below, I offer a simple model that rationalizes this expectation. Whether it's the model FOMC members have in their heads, I'm not sure. (Well, I happen to know in the case of two FOMC members, but I won't share this here.)

Formally, I have in mind a simple OLG model (see, here). The model is Non-Ricardian (the supply of government debt is viewed as private wealth). The model's properties are more Old Keynesian than New Keynesian. The model is also consistent with Monetarism, except with the supply of base money replaced with the supply of outside assets (i.e., all government securities--cash, reserves, bills, notes and bonds).

So, I'm thinking about my model beginning in an hypothetical stationary state. The real economy is growing at some constant rate (say, zero). The supply of outside assets consists of zero interest securities (monetary policy is pegging the nominal interest rate to zero all along the yield curve). This supply of "debt" is also growing at some constant rate. Debt is never repaid--it is rolled over forever. Indeed, the nominal supply of debt is growing forever. New debt is used to finance government spending. The real primary budget deficit is held constant. The government is running a perpetual budget deficit via bond seigniorage; see here. The steady-state inflation rate in this economy is given by the rate of growth of the supply of nominal outside assets. (It is also possible that the inflation rate is determined by shifts in the demand for USTs; see here, for example). The real interest rate (on money) is negative.

OK, now let's consider a large fiscal shock in the form of a one-time increase in the supply of outside assets (i.e., a helicopter drop of money that is never reversed). The effect of this shock is to induce a transitory inflation (a permanent increase in the price-level). An increase in the nominal supply of money at a given interest rate at full employment makes the cost of living go up -- it makes the real debt go down. And oh, by the way, the debt-to-GDP ratio is declining thanks in part to inflation:

This is despite the persistent negative real interest rate prevailing in the economy. I mean, what else might one imagine from a one-time injection of money? Is this is what the Fed is thinking? (This is what I'm thinking!) Note: an increase in the interest rate in this model would unleash a disinflationary force, but this would only serve to speed up the transition dynamic.

As it turns out, this simple story seems consistent with what I take to be John's preferred theory of inflation. The large fiscal shock here is unaccompanied by the prospect of future primary budget surpluses. The effect is to increase the price level (i.e., a temporary inflation). Maybe the Fed has John's FTPL model in mind?

Neither of these stories line up particularly well with the New Keynesian model, which emphasizes interest rate policy as *the* way inflation is controlled. There are, however, many strange things going on in this model. First, while no explicit attention is paid to fiscal policy, the fiscal regime plays a critical role in determining model dynamics (basic assumption is lump-sum taxes and Ricardian fiscal regime). Second, the Taylor principle that is needed to determine a locally unique rational expectations equilibrium is an off-equilibrium credible threat to basically blow the economy up if individuals do not coordinate on the proposed equilibrium (I learned this from John here.) By the way, Peter Howitt provides a different (and in my view, a more compelling) explanation for the "Taylor principle" here--published a year before Taylor 1993. Given these shortcomings, why are we even using this model as a benchmark? This is another good question.

John presumably picks this model because he sees no better alternative for modeling monetary policy via an interest rate rule. If he wants an alternative, he can read my paper above. Or, he can appeal to his own class of models extended to permit a liquidity function for USTs. These models easily accommodate stable inflation at negative real rates of interest. But whether this is how FOMC members organize their thinking, I'm not sure.

In any case, John picks an off-the-shelf NK model and assumes that it adequately captures what is in the mind of many FOMC members. Let's see what he does next (Modeling the Fed).

He writes: "The Fed clearly believes that once a shock is over, inflation stops, even if the Fed does not do much to nominal interest rates. This is the "Fisherian" property. It is not the property of traditional models. In those models, once inflation starts, it will spiral out of control unless the Fed promptly raises interest rates." [I think he meant "threatens to raise interest rates.]

Comment 1: I'm not sure what he means by a "Fisherian" property. (Note: the Fisher equation holds in the OLG model I cited above--though the real rate of interest is not generally fixed in those settings.)

Comment 2: Conventional models? I presume he means Woodford's basic NK model. It seems likely to me, however, that FOMC members may have other "conventional" models in their heads -- like the Old Keynesian model or the Old Monetarist model--both of which continue to be taught as standard fare in undergraduate curricula.

OK, so John considers a very basic IS-PC model and considers two alternative hypotheses for how inflation expectations are determined. The first hypothesis is a simple adaptive rule (see also Howitt's work above). The second hypothesis is perfect foresight (rational expectations) -- which, by the way, implicitly embeds knowledge of the Ricardian fiscal regime.

Under the adaptive expectations model, inflation explodes. Under the rational expectations hypothesis, inflation largely follows the Fed's actual forecast. Maybe this is what the Fed is thinking? The Fed has rational expectations?

Except that I'm not really sure what this means. John does give us a further hint though. He goes on to say "Not only is the Fed rational expectations, neo-Fisherian, it seems to believe that prices are surprisingly flexible!"

Right. So the Neo-Fisherian hypothesis is that to get a permanently lower rate of inflation, the Fed must (at least eventually) lower its policy rate (and vice versa to raise the rate of inflation). I've questioned this hypothesis in the past (see here). But what's going on here now? Is John suggesting that the FOMC is made up of closet Neo-Fisherians? Steve Williamson would no doubt be pleasantly surprised.

John writes: "The proposition that once the shock is over inflation will go away on its own may not seem so radical. Put that way, I think it does capture what's on the Fed's mind. But it comes inextricably with the very uncomfortable Fisherian implication. If inflation converges to interest rates on its own, then higher interest rates eventually raise inflation, and vice-versa."

No, I'm afraid the conclusion that inflation is transitory (even with negative real rates) is NOT inextricably linked to the Neo-Fisherian proposition. It is only inextricably linked this way in a class of economic models that: [1] are pretty bad; and [2] highly unlikely to be in the heads of most FOMC members.

Saturday, January 29, 2022

The Inflation Blame Game

Inflation is back together with a new season of America's favorite sport: zero-contact, finger-pointing. I thought I'd sit back and share a few thoughts with you on the subject on this cold Saturday afternoon. Use the comments section below to let me know what you think.

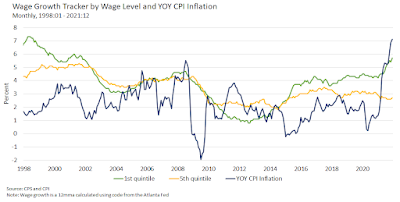

In one corner, I see some pundits somehow wanting to blame the 2021 inflation on workers. Workers are somehow forcing their improved bargaining positions on employers, raising the costs of production, with some or all of these costs passed on to consumers. Then, as workers see their real wages erode, the cycle begins anew begetting the dreaded "wage-price spiral." Those pesky workers.

There's no doubt something to the idea that wage demands can lead to higher prices (and why shouldn't workers want cost-of-living adjustments?) But what is the evidence that this behavior was the impulse behind the 2021 inflation?

While it's difficult to tell just by eye-balling the data, I think it's reasonable (under this hypothesis) to see wage growth precede (or at least be coincident with) inflation. Unfortunately (for this hypothesis), this is not what we see in the data. In the diagram below, use the Atlanta Fed's Wage Growth Tracker to construct nominal wage inflation for the bottom (green) and top (yellow) wage quintiles. This is plotted against CPI inflation (blue).

Another problem for this hypothesis is that wage inflation is moving in the wrong direction for the top three wage quintiles over the Covid era. What we see here is a clear acceleration in the rate of inflation, followed by modest acceleration in wage inflation for the bottom quintile and a deceleration in wage inflation for the top quintile. In 2021, real wages across all quintiles declined (according to this data). So much for increased worker bargaining power. [Note: it is quite likely that net income for the bottom one or two quintiles increased, thanks to government transfers.]

On the other side of the political spectrum, we see pundits and politicians blaming the 2021 inflation on "corporate greed." Framing the issue in terms of "corporate greed" is not especially helpful, in my humble opinion. The substantive part of this claim is that large firms were somehow able to leverage their pricing power in 2021 into higher profit margins and record corporate profits. There is, in fact, some evidence in support of this. The diagram below plots profit margins for firms in the Compustat database. Profit margin below is computed on an after tax basis (net income divided by sales). The data is divided between large and not-large firms. Large firms are those in the top 10% of sales volume.

By this measure, profit margins seem remarkably stationary over long periods of time. There is some evidence of a modest secular increase in margins c. 2003. Large firms have higher margins. But the part I want to focus on here is near the end of the sample. Profit margins for 90% of firms seem close to their historical average. We see some evidence that profit margins for the top 10% of firms increased in 2021. But this increase peaked in Q3 and then declined back to historical norms in Q4. While the spike in profit-margins likely contributed to inflation, it hardly seems like a smoking gun. And the Q4 reversion to the mean suggests that "corporate greed" is not likely to be a source of inflationary pressure in 2022.

Well, if workers and firms are not to blame, then who or what is left? There's the C-19 shock itself, of course, along with the effects it has had on the global supply chain. But the 19 in C-19 refers to the year 2019 (and 2020). We're talking about 2022 here. Sure, the supply chain issues are still with us. But at most, I think they account for a substantial change in relative prices (goods becoming more expensive than services) and an increase in the cost-of-living (an increase in the price-level--not a persistent increase in the rate of growth of the price-level).

While the factors above no doubt contributed in some way to the 2021 inflation dynamic, let's face it--the size and persistence of the inflation was mainly policy-induced. The smoking gun here seems to be the sequence of the C-19 fiscal transfers. As we know, this had the unusual and remarkable effect of increasing personal disposable income throughout most of the pandemic. The Fed also had a role to play here because it accommodated the fiscal stimulus (normally, one might have expected a degree of monetary policy tightening to partially off-set the inflationary impulse of fiscal stimulus). Below I plot retail sales (actual vs trend) and the timing of the fiscal actions.

I used retail sales here (I think I got this from Jason Furman), but the picture looks qualitatively similar using PCE (the path of nominal PCE went above trend in 2021 and not earlier in the way retail sales did). Just eye-balling the data above, I'd say the CARES Act was a major success (especially under the circumstances). The subsequent two programs might have been scaled back a bit and/or targeted in a more efficient manner. And, knowing what we know now, the Fed could have started its tightening cycle in 2021.

Having said this, I wouldn't go so far as to say these were flagrant policy mistakes--given the circumstances. If there was a policy mistake, it was in not having a well-defined state-contingent policy beforehand equipped to deal with a global pandemic. Not having that plan in place beforehand, I think monetary and fiscal policy reacted reasonably well.

Policymaking in real-time is hard. And policy, whether formulated beforehand or not, must necessarily balance risks. There was a risk of undershooting the support directed to households. We saw this during the foreclosure crisis a decade ago. And there was a risk of overdoing it in some manner. Keep in mind that it was not clear when the legislation was passed how 2021 would unfold. Similarly, for the Fed--perhaps still feeling the sting of having moved too soon and too fast in the past, hopeful that inflation would decline later in the year--delayed its tightening cycle to 2022. It wasn't perfect. But taken together, the economic policy responses had their intended effect of redistributing income to those who suffered disproportionate economic harm during the pandemic.

Finally, what does all this mean for inflation going forward? Well, as I suggested above, I don't think we have to worry about a wage-price spiral (the fiscal policy I think is necessary to support such a phenomenon is not likely to be present). Profit margins appear to be declining (reverting to their long-run averages). The money transfers associated with the last fiscal package are gone for 2022. No big spending bills seem likely to pass in 2022. For better or worse, we're talking a considerable amount of "fiscal drag" here (although, some have pointed to how flush state government coffers are at the moment). Hopefully (fingers crossed), supply-chain problems will continue to be solved. If so, then all of this points to disinflation (a decline in the rate of inflation) going forward. Some recent promising signs as well: [1] month-over-month CPI inflation has declined for two consecutive months (November and December); and [2] the ECI (employment cost index) decelerated in Q4 of 2021. (These numbers are notoriously volatile, so don't put too much stock in the direction. But still, it's better than seeing them go the other way.)

Some caveats are in order, of course. In December 2020, I suggested we prepare for a "temporary" burst of inflation in 2021. While this came to pass, the level of inflation surprised me (to be fair, I hadn't incorporated the ARP in my assessment, but even if I had, I think I still would have been surprised). Moreover, I was also surprised by the persistence of inflation--I thought it would decelerate more rapidly (even given the ARP). This just serves to remind me how bad I am at forecasting. Someone recently mentioned a great quote by Rudi Dornbusch: "In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster you thought they could." I can relate to this.

Inflation may turn out to be more persistent that I am suggesting. But how might this happen, given the disinflationary forces I cited above? One reason may have to do with the tremendous increase in outside assets the private sector has been compelled to absorb--the increase in the national debt has manifested itself as an increase in private sector wealth. Jason Furman sees this as "excess saving." The question going forward is whether the private sector will be compelled to spend this (nominal) wealth (it already has done so, as my chart above shows) or continue to save (not spend) it? It is possible that this "pent up demand" will be spent over a prolonged period of time. The effect of this would be to keep inflation elevated higher than it would otherwise be (serving to reduce real nominal wealth). How long this might take, I have no idea. But even so, it seems clear that the effect cannot persist indefinitely. At some point the debt-to-GDP ratio will decline to its equilibrium position (D/Y has already started to decline; see here).

Another reason why inflation forecasts should be discounted is that it's very difficult to forecast future contingencies. What might happen, for example, if Russia invades the Ukraine this year? Events like these will create disruptions and there's not much monetary and fiscal policy can do about them. But whatever happens, I think the long-run fiscal position of the U.S. will remain anchored (Americans will demand this). And remember, the Fed is bound by its Congressional mandates to keep inflation "low and stable." The Fed's record on inflation since the Volcker years has been pretty good. I'm betting that the record will be equally good over the next 10 years.

***

PS. I see some people out there strongly asserting it is a "fact" that fiscal policy did not cause the 2021 inflation (see here, for example). The reason, evidently, is because inflation is a global phenomenon. There's something to this, of course. After all, C-19 is a global pandemic. But this reasoning nevertheless seems faulty to me. First, the USD is the global reserve currency. It's quite possible that the U.S. exported some of its inflation to the world (much in the way it did in the 1970s). Second, many other countries (like Canada, for example) adopted similar fiscal policies. Those countries with less expansive fiscal policies also displayed lower inflation, as far as I know. Rather than deflect the blame, we should own it here. Fiscal policy had a lot of positive effects too (e.g., lowering child poverty). The challenge, as always, is to develop ways to calibrate these policies in a more effective manner.