Remember when the Fed's most pressing policy concern was missing their 2% inflation target from below for most of the decade following the financial crisis of 2008-09? The concern never failed to puzzle me in all my time at the St. Louis Fed. I once let out how I really felt:

Well, inflation returned. But not exactly for the reasons I was expecting. What happened?

Shocks

What happened was COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war. These two shocks were large, disruptive, and persistent. A great many people died. Large parts of the economy were shut down with the hope of slowing the spread of the virus so as not to overwhelm our limited ICU capacity. The leisure and hospitality sector was crushed, and other sectors as well. There was a massive (and highly unusual) reallocation of production and consumption away from services to goods--a phenomenon that has not fully reversed to this day. We learned about the delicate and interconnected nature of global supply chains. People modified their behavior in dramatic ways. Work-from-home seems here to stay. And then, of course, as if a global pandemic was not enough, Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, leading to the usual sickening consequences of war: death, destruction, and displacement--as well as energy disruptions and food shortages that reverberated across the global economy.

This is not, of course, the only thing that happened. We also had policy responses.

Policy: What was needed

I want to limit attention to economic policy here (health policy is another matter). The COVID-19 shock disrupted some sectors of the economy more than others. Some sectors, like leisure and hospitality were virtually shut down. But in many other parts of the economy, people were able to work from home. Since not many people purchased pandemic-insurance, a large number of Americans were in for a whole lot of economic hurt. Most of those adversely affected were in the bottom half of the income distribution. What could and should have been done?

I should like to think that most Americans would have been in favor of a social insurance program that supported those most in need; i.e., targeted transfers for as long as the pandemic remained disruptive. Most people would have recognized that this is the right thing to do. And even those few who seemingly do not care much for their fellow Americans might have recognized how redistribution would have been desirable, perhaps even necessary, to maintain social cohesion. We should not have wanted a replay of what happened in the last crisis, where the financial sector was bailed out while American many households were largely left flailing in the foreclosure winds that blew in the aftermath of 2008-09.

How might such a program be financed? A consumption tax would have been one way. Imagine a "transitory" 5% federal sales tax to fund a targeted transfer program. The program parameters could, in principle, be calibrated in a manner that requires little or no adjustment in the deficit. Ideally, such an emergency program would have already been put in place. (As far as I know, there is still no such plan in place--a significant policy failure, in my view.)

How might things have played out with such a policy, given the sequence of shocks that unfolded? To a first approximation, my guess is "probably not much different." With the balanced-budget policy described above, inflation would have almost surely been lower. Imagine shaving 300-500bp off the "inflation hump" we've experienced so far:

We would almost surely still have had some inflation stemming from supply disruptions and energy

costs (associated with the war). But inflation would have been less pronounced. Naturally, rather than complaining about high inflation, people would instead have

been complaining about high consumption taxes. ("They told us they'd be

transitory!") There's no such thing as a free lunch.

Under this higher-tax/lower-deficit policy, most Americans would have felt worse off relative to 2019. The blame for this feeling, however, properly lies with the shocks and not the policy response. Yes, work-from-home types would not have received transfers and they would have been paying more for goods and services. This is the nature of redistribution, which I believe most people would have supported.

Policy: What we got

To a large extent--and all things considered--we pretty much got what was needed: a set of redistributive policies with transfers targeted (mostly) to the bottom half of the income distribution (yes, yes, we can talk at length about how things could have been done better). Except that there was no surtax to fund the transfers. Our representatives in Congress chose to deficit-finance the programs. The resulting large quantity of treasury paper had to be absorbed by the private sector at a time supply was constrained and interest rates were not permitted to rise (I'll get to monetary policy in a moment). How does one not expect some additional inflation in this case? So, instead of a "transitory" consumption tax, we got a "transitory" inflation tax. There's no free lunch.

By the way, by "transitory" I mean to say that inflation is expected to revert to target, instead of remaining elevated or even increasing. In the fall of 2020, I expected a "temporary" inflation (see here) because I thought the supply disruptions and CARES Act were not permanent. Inflation turned out to be higher and more persistent than I expected. But the supply disruptions have largely alleviated and the ARP expired at the end of 2021 (though the RUS-UKR war continues). Up until recently, I remained optimistic that--absent further shocks and with responsible fiscal policy--inflation would make its way back down to target in 3-5 years without a recession. I'm not as optimistic today, but let me return to this below.

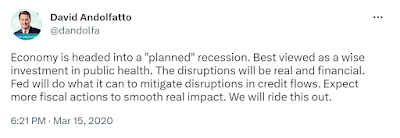

What about monetary policy? Well, I was very pleased with the way the Fed calmed financial markets in March 2020, as I expected it would.

Well done, Fed. But what about monetary (interest rate) policy?

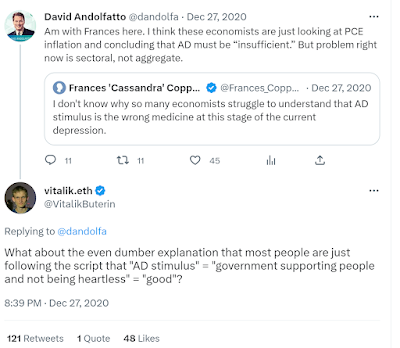

Well, to be honest, monetary policy seemed a bit bonkers. Lowering the policy rate in response to recession engineered by a manufactured shutdown did not make much sense to me. My view was more in line with Michael Woodford's, as expressed here in his 2020 Jean Monnet lecture. What was needed was insurance, not stimulus. And this insurance needs to be delivered through fiscal policy.

My own view is that many economists could not resist interpreting the severe decline in output as reflecting a conventional "output gap." To be fair, there may very well have been a decline in aggregate demand in the first half of 2020. The economic outlook at the time was very uncertain, which likely increased the desire for precautionary savings. Remember, monthly inflation rates for March, April and May of 2020 were negative. The monthly inflation rate only became positive in June 2020 (5.4% annualized rate), though it remained fairly subdued for most of 2020.

Heading into 2020, the Fed's policy rate was around 1.6%. Was it really necessary to lower it any further? Especially in light of the fiscal transfers taking place throughout 2020? But apparently, in the minds of some, perhaps even most, the economy needed "stimulating."

In any case, it seems clear now, in retrospect at least, that the cut should probably not have happened or, conditional on happening, should have been quickly reversed once the financial panic had subsided. The main effect of interest rate policy according to many was an undesirable asset-price boom (stocks, bonds, and real estate). The increase in private sector wealth coming from higher asset valuations surely added some fuel to the inflationary fire.

We can now see how that Fed-induced wealth effect is being undone. The rapidity of the rise in the Fed's policy rate is wreaking havoc on wealth portfolios. This is not a huge concern to the extent the policy is just reversing an undesirable asset-price inflation. But to the extent that these assets sit on bank balance sheets, to the extent these positions are not hedged against duration risk, to the extent that depositors are skittish, and to the extent that capital buffers are running low, then the banking system--or at least parts of it--are subject to runs. We are seeing this play out now in the United States.

Where are we heading?