Miles Kimball believes that the zero lower bound (ZLB) constitutes a significant economic problem (he is not alone, of course). His viewpoint is expressed clearly in the title of his post: America's Huge Mistake on Monetary Policy: How Negative Interest Rates Could Have Stopped the Recession in its Tracks.

That's quite the bold claim. But what is the reasoning behind it? Yes, I can see how a price floor can distort allocations and make things worse than they otherwise might have been if prices were flexible. But would interest rate flexibility really have prevented the recession?

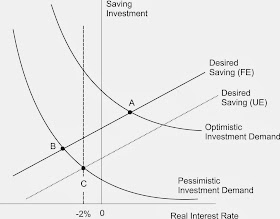

Suppose I wanted to teach this idea in my intermediate macro class, using conventional tools. How would I do it? (Maybe it can't be done, but if not, then someone present me with an alternative.) I think I might start with the following standard diagram depicting the aggregate supply and demand for loanable funds (the foundation of the so-called IS curve):

Suppose the economy starts at point A. (I am assuming a closed economy, so aggregate saving equals aggregate investment.) The real interest rate is positive.

Next, suppose that there is a collapse in investment demand. For the purpose of the present argument, the reason for this collapse is immaterial. It might just be psychology. Or it might be the consequence of a rationally pessimistic downward revision over the expected future after-tax return to capital spending. In either case, the economy moves to a point like B, assuming that the interest rate is flexible.

But, suppose that the Fed is credibly committed to a 2% inflation target. Moreover, suppose that the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero (the ZLB). Then, when the nominal interest rate hits the ZLB, the real rate of interest is -2%.

If this was a small open economy, the gap between desired saving and desired investment at -2% would result in positive trade balance (as domestic savers would divert their saving to more attractive foreign investments, over the dismal domestic investment opportunities). But in a closed economy, saving must equal investment and so, as the story goes, domestic GDP must decline to equilibrate the market for loanable funds. As domestic income falls (and as people become unemployed), desired domestic savings decline (the Desired Saving function moves from the Full Employment position, to the Under Employment position, in the diagram above).

Now, if this is a fair characterization of the situation as Miles sees it (and it may not be--I am sure he will let us know), then I would say sure, I can see how the ZLB can muck things up a bit. The economy is at point C, but it wants to be at point B (conditional on the pessimistic outlook).

But while point B might constitute an improvement over point C, it does not mean an end to the recession. Domestic capital spending is still depressed, and ultimately, the productive capacity of the economy will diminish. I'm not sure I see how a negative interest rate is supposed to prevent a recession, or get the economy out of a recession, if the fundamental problem is the depressed economic outlook to begin with.

If anyone out there has another way of looking at the problem, please send it along.

***

Update: Here is a reply from Gerhard Illing:

That's quite the bold claim. But what is the reasoning behind it? Yes, I can see how a price floor can distort allocations and make things worse than they otherwise might have been if prices were flexible. But would interest rate flexibility really have prevented the recession?

Suppose I wanted to teach this idea in my intermediate macro class, using conventional tools. How would I do it? (Maybe it can't be done, but if not, then someone present me with an alternative.) I think I might start with the following standard diagram depicting the aggregate supply and demand for loanable funds (the foundation of the so-called IS curve):

Suppose the economy starts at point A. (I am assuming a closed economy, so aggregate saving equals aggregate investment.) The real interest rate is positive.

Next, suppose that there is a collapse in investment demand. For the purpose of the present argument, the reason for this collapse is immaterial. It might just be psychology. Or it might be the consequence of a rationally pessimistic downward revision over the expected future after-tax return to capital spending. In either case, the economy moves to a point like B, assuming that the interest rate is flexible.

But, suppose that the Fed is credibly committed to a 2% inflation target. Moreover, suppose that the nominal interest rate cannot fall below zero (the ZLB). Then, when the nominal interest rate hits the ZLB, the real rate of interest is -2%.

If this was a small open economy, the gap between desired saving and desired investment at -2% would result in positive trade balance (as domestic savers would divert their saving to more attractive foreign investments, over the dismal domestic investment opportunities). But in a closed economy, saving must equal investment and so, as the story goes, domestic GDP must decline to equilibrate the market for loanable funds. As domestic income falls (and as people become unemployed), desired domestic savings decline (the Desired Saving function moves from the Full Employment position, to the Under Employment position, in the diagram above).

Now, if this is a fair characterization of the situation as Miles sees it (and it may not be--I am sure he will let us know), then I would say sure, I can see how the ZLB can muck things up a bit. The economy is at point C, but it wants to be at point B (conditional on the pessimistic outlook).

But while point B might constitute an improvement over point C, it does not mean an end to the recession. Domestic capital spending is still depressed, and ultimately, the productive capacity of the economy will diminish. I'm not sure I see how a negative interest rate is supposed to prevent a recession, or get the economy out of a recession, if the fundamental problem is the depressed economic outlook to begin with.

If anyone out there has another way of looking at the problem, please send it along.

***

Update: Here is a reply from Gerhard Illing:

Hello David,

I am not sure if that is what you are asking for, but at

least within the standard NKM framework (with negative time preference shocks)

it is fairly straightforward to illustrate that eliminating the ZLB would

allow monetary policy to perfectly stabilize the economy at the natural rate. I

just finished a sort of “textbook” version (allowing for an explicit analytical

solution) of that framework.

In terms of your graph (with the nominal interest rate as

adjustment tool to time preference shocks under sticky prices) it looks as

follows:

Presumably you are not happy with the NKM framework as a

realistic description of current issues - but within that logic, these

arguments follow naturally, in particular if you are on the “secular

stagnation” trip.

And here is a further elaboration, provided by Gerhard:

I think the argument goes like this :

ReplyDeleteonce you are at C without any possibility to go to B, output falls which depresses investment demand even further. In a Samuelson-like theory, an employment fall leads to a lower natural interest rate. So in your graph, the investment demand curve shifts further to the bottom.

At least with no ZLB, no unemployment, which means you just have to wait for the reasons behind the initial fall in investment demand to disappear.

Correct me if you think I'm wrong...

I am not sure why a decline in output should cause a decline in the investment demand schedule. If anything, one might expect it to increase, since lower output means less capital, and less capital means a higher marginal product of capital? Anyway, I want a diagram. Show me a diagram!

DeleteI think they would reply that a lasting fall in expected returns can only be the result of a failure to lower the real interest rate further. Otherwise, the economy naturally springs back to point A. Thus, every lasting recession has to be caused by a policy failure. Negative-rate e-currency is simply a way of saying, "there is no excuse for allowing a long recession to occur".

ReplyDeleteThe question is why their model doesn't allow for expected returns to vary. I think this has something to do with assumed fixed growth rates of technology and endowments (i.e. a devotion to "trend").

So I think the question is, who has a good model for variation in expected returns, and does it make more sense than the theory of "trend" growth? I think complex adaptive systems thinking is a good way to explain the former, but, of course, its very complexity doesn't allow for a formalized modelling approach.

" I think I might start with the following standard diagram depicting the aggregate supply and demand for loanable funds"

ReplyDeleteThats not loanable depicted funds is it? Thats the interest rate on reserves. I cant borrow reserves off the fed and commercial banks certainly dont lend at near 0%. A loanable funds rate compiled from lending data would be more like at least 5%.

The desired saving and desired investment functions provide the foundation for the IS curve. What you call this market is not too important. I think I borrowed this terminology from Mankiw's text. Just call it the goods market, if you'd rather.

DeleteDavid:

ReplyDelete1. Jeez! Why do you put the interest rate on the horizontal axis?? Everybody else puts it on the vertical axis! We can't read it that way up! Are you trying to break our necks? Or break our computer screens? (Everybody looking at your picture is either twisting his head sideways or holding his computer screen sideways.)

2. Lots of things can go wrong with an economy. Investment can be too low or too high. Saving can be too high or too low. Banks can go bust. Sometimes we can fix those things and sometimes we can't, or won't. But they didn't ought to cause a recession. We don't have to add a macro/business cycle injury to a micro/growth injury.

3. Maybe those pessimistic beliefs are not pessimistic, and that investment demand curve is just the way it should be.

4. Maybe the recession itself is what caused, or is part of the cause, of the pessimistic investment demand. It becomes a self-fullfilling belief. By allowing negative nominal interest rates we eliminate the bad equilibrium.

Nick,

DeleteIt was Marshall who got the axes wrong, not me. When we derive desired saving and investment, the real interest rate is the independent variable, no?

In any case, you did not answer my question of how to exposit the idea to undergrads. Just draw an IS curve, with R chosen by policy. The IS curve shifts in. How does changing R "fix" the fact that the IS curve has shifted?

Isn't traditional IS-LM analysis, where an IS curve shift makes you want to shift the LM curve to go back to the initial level of output, but you can't because the LM curve is flat on the Y axis?

Deletehttp://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2011/10/09/opinion/100911krugman2/100911krugman2-blog480.jpg

I just exposed it like that two weeks ago to my students, they seemed to respond well.

In that graph, the natural interest rate is where LM would cross IS if it were a straight line. So negative.

Yes, that is also true in my diagram: lower the interest to get point C. But that does not cure the fact that investment demand is depressed, does it?

DeleteNo it doesn't but at least it prevents the bad equilibrium where investment demand depresses further, if you think that investment is somewhat linked to output expectations.

DeleteI think we need more than IS-LM to understand secular stagnation...

David, here is an attempt to answer your question using a modified IS-LM model. http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2012/02/can-raising-interest-rates-spark-robust.html

ReplyDeleteDavid, your exposition here is identical to mine, except you used the IS-LM representation. The answer is the same: lowering the interest further will not cure the depression.

DeleteDavid, take another look at my figure. It shows an output gap that is directly tied to interest rate gap. Consequently, if the Fed were somehow able to lower its policy rate to the negative natural rate level the output gap would be closed. In terms of my graph, it would be shifting the blue LM line down until it hit the intersection of the green IS line and the red full employment line. So it does show how to end the slump (i.e. a return to full employment).

ReplyDeleteThe thing is, in David A.s first graph, the desired saving curve is upward sloping. Now with a lower interest rate, investment/saving is lower. So the recession maybe cured but the trajectory of potential output is lower.

DeleteIn the IS LM setup, that doesn't appear. GDP goes back to its natural level through consumption, as desired savings fall, not through investment.

So investment is permanently lower.

David,

DeleteWhat your analysis misses is the fact that saving and investment are permanently lower. Thus, even at full employment, we will have (in the long run) lower potential GDP. There is a permanent gap between actual and trend GDP. Lowering the interest rate will not fix this.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteDavid, that was not that original question. You asked to be shown how a negative policy rate could end a recession and restore full employment. And it is straightforward to show with an IS-LM model that has a full-employment line.

ReplyDeleteRegarding long-run implications, there is no reason to conclude desired saving and investment will be permanently lower. The return to full employment will improve economic expectations and increase desired investment by firms. This should raise the IS curve back up and push up the natural interest rate. The Fed would follow by raising its policy interest rate. This is the story Miles Kimball has been telling and I don't think it is that controversial. It happens during 'normal' recessions that don't breach the ZLB and should happen here too. I graphically show this story in this first figure of this post: http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2014/01/miles-and-scotts-excellent-adventure.html

Yes, maybe I wasn't as clear as I could have been. Full employment is easy. Just ask the Soviets how they achieved it. I was talking about the gap between actual and potential GDP. I should have said so.

DeleteI haven't read Miles' piece. Am looking forward to reading it, but for now, your statement "This should raise the IS curve back.." sounds more like wishful thinking than a theoretical result. I'm looking forward to being proven wrong!

David, I'm sorry but I do not see any theory in the post you directed me to. All I see is an asserted time-path for variables. I know Miles has the model living somewhere, I just need to find it.

DeleteDavid, I was directing you to the post to demonstrate how the time path would look given Miles story. The point was to show the story isn't about natural (and actual) interest rates remaining negative for long, but returning to positive values. Regarding wishing the IS curve back, again this is borne out in the data. Interest rates at the business cycle frequency are generally procyclical. So unless something suddenly happened to the LR natural interest rate to make it negative, there is no reason to presume interest rates would remain negative. They too would follow the recovery.

DeleteDavid, as I suspected, you are just assuming some form of automatic mean reversion. You justify it on the basis of what has happened in the past, but it is not a theoretical result. My point stands: if there is a highly persistent decline in the investment demand schedule, then lowering the interest rate will not cause the curve to shift back. It shifts back for other reasons -- a shift in expectations on the return to capital spending, an increase in government infrastructure spending, etc.

DeleteDavid, the argument is that the return to full employment will change household and firm expectations and therefore shift the curve. It should not be a controversial claim because this theory is borne out in the data--interest rates are procyclical for a reason! This is not a naive appeal to mean reversion. Your view, on the other hand, makes a strong assumption--that investment will stay depressed even when interest rate fully adjust--that has little empirical evidence.

ReplyDeleteDavid,

DeleteThat's fine, but like I said -- there is no *theoretical* reason to assume that a move to full employment will *shift* that curve. You may argue it on empirical grounds (which I, together with Keynes and Roger Farmer may dispute), but not on theoretical grounds.

I do not agree with what you say beyond that. Interest rates are procylical in my theory too -- the investment demand function slopes downward, after all. The "strong" assumption that investment can remain depressed for long periods of time is not inconsistent with data that I am aware of.

Not sure if this is what you are looking for, but here I use a modified IS/LM to derive historical time preferences. It could also be used to demonstrate the impact of the lower zero bound, which is excess in savings and decline in borrowing: tinyurl.com/qzp4h3f

ReplyDeleteAlso, I agree with the broader point that negative interest rates may be ill-thought. Here's why tinyurl.com/kfdgkae

Very interesting diagrams. Which diagramming software did you use to draw these diagrams. I hope its not visio. Since its not simply affordable. Please let me know the diagram software you use if it is a platform independent software.

ReplyDeleteRegards,

Creately