According to Gross, the Fed's low interest rate policy constitutes a form of "financial repression." His argument, as far as I can tell, goes as follows. Long-term prosperity depends on the stock of productive capital. The stock of productive capital is augmented by investment (the flow of newly produced capital goods). Investment is financed out of saving. Low interest rates discourage saving. Therefore, low interest rates are ultimately a prescription for secular stagnation.

Gross claims that "no model will lead to this conclusion." I'm not exactly sure what he means by that. I think what he means "forget about theory, let's just look at the facts." Unfortunately, facts do not always speak for themselves.

So what sort of evidence does he select to support his conclusion? He begins by noting that inflation-adjusted interest rates (on high-grade bond instruments, I presume) were on average negative over the period 1930-1979 and on average positive since then (thanks to Volcker) until recently. Here's what the data looks like since the end of the Korean war (FRED only gives me the interest rate series since then).

The blue line plots the nominal yield on a one-year treasury, the red line plots the one-year CPI inflation rate. Blue minus red gives us a measure of the realized inflation-adjusted return on a nominally risk-free security. Returns were relatively high in the 1960s, 1980s, 1990s, and relatively low in the 1970s, 2000s, and 2010s (so far).

In relation to this observation, Gross writes approvingly of Fed policy decisions in the early 1980s:

But then Paul Volcker turned the bond market upside down and ever since (until 2009), financial markets enjoyed positive real yields and a kick in the pants boost to other asset prices, as those yields gradually came down and increased the present value of bonds, stocks and real estate.This is a bizarre statement in some respects. First, as the data above makes clear, it was nominal yields that gradually came down--real yields remained elevated for two decades after the event. Second, he evidently does have a model of how a policy-induced increase in the nominal interest rate leads to prosperity: as yields march downward from an elevated level, capital gains are realized in a broad range of asset classes. This is a bizarre argument both in its own right and because it ignores the initial capital losses realized on wealth portfolios when the policy rate is suddenly increased.

So, no, I don't think that model makes much sense. But if so, then how do we make sense of the data? The fact is that the U.S. economy generally did prosper after the 1981-82 recession. Most economists attribute this subsequent era of prosperity in part to the fact that Volcker's policies ushered in an era of low and stable inflation. Jacking up the interest rate was just a temporary measure to bring inflation down. And once inflation began to drift down, nominal yields declined because of the Fisher effect. The fact that real yields remained elevated was just the by-product of an accelerated growth in productivity (after the 1970s productivity slowdown) that likely had little to do with monetary policy.

But maybe this conventional interpretation is incorrect. Could Gross be on to something? Maybe there is a model that justifies his conclusion. I've been thinking about this lately, wondering just what such a model would look like. Here is what I came up with.

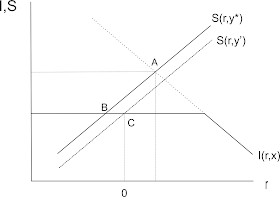

Consider a textbook macro model. Let S(r,y) denote the supply of saving, assumed to be increasing in real income y (GDP) and the real interest rate r. Let I(r,x) denote the demand for investment, assumed to decreasing in the real interest rate r and increasing in the expected productivity of capital investment, x.

In a closed economy, domestic saving must equal domestic investment, so S(r,y) = I(r,x). This equation gives us the famous IS curve: the locus of (y,r) combinations consistent with S=I. This relation exists, in one form or another, in virtually every macro model I'm aware of.

The neoclassical view is that the market, left to its own devices, will determine a "full employment" level of income, y*. With y* so determined, the equilibrium rate of interest r* is determined by market-clearing in the loanable fund market, S(r*,y*) = I(r*,x).

Business cycles are generated by fluctuations in the x. High x is associated with optimism, low x with pessimism (over the expected return to capital spending). The diagram below demonstrates what happens when the economy switches from an optimistic outlook to a pessimistic outlook. Let point A denote the initial equilibrium position. A decline in x to x' shifts the investment demand schedule downward. Lower investment demand puts downward pressure on the interest rate--the economy moves along the saving schedule from point A to B. If depressed expectations persist, then the lower level of investment leads to a lower stock of productive capital. This has the effect of depressing GDP. As income declines from y* to y', the saving schedule shifts down and the economy moves from point B to C.

Point C is characterized by lower income, lower investment, lower saving and a lower real interest rate. This is the neoclassical explanation for why periods of why real interest rates are procyclical. Low interest rates are not the product of "financial repression." They are symptomatic of a depressed economic outlook. And any attempt to artificially increase the real interest rate is going to make things worse, not better. One cannot legislate prosperity by increasing the interest rate.

Now, if I understand Gross correctly, he seems to be saying that present circumstances are not the byproduct of depressed expectations. The problem is that the Fed is keeping the real interest rate artificially low. Let's try to interpret this view in terms of the following diagram. The economy naturally wants to be at point A, where the interest rate is higher, along with saving, investment and income. But the Fed is keeping the interest rate artificially low--at zero, in the diagram below.

The effect of the zero interest rate policy is to discourage saving. While the demand for investment is high (point D), there's not enough saving to finance it (point B). As such, the level of investment falls from A to B. The lower investment eventually translates into lower GDP. As income declines, the saving schedule shifts down and the economy eventually settles at point C. This is secular stagnation brought about by the Fed's financial repression.

So is this a sensible argument? There is a problem with it that Gross touches on in his piece when explaining how low interest rates are harmful:

How so? Because zero bound interest rates destroy the savings function of capitalism, which is a necessary and in fact synchronous component of investment. Why that is true is not immediately apparent. If companies can borrow close to zero, why wouldn’t they invest the proceeds in the real economy? The evidence of recent years is that they have not.Indeed, the logic of the argument is not apparent at all. With interest rates so low, the business sector should be screaming for funds to finance huge new capital expenditures (point D in the diagram above). But they are not. Why not? At this stage, he simply abandons the logic and refers to the evidence. As if the evidence alone somehow supports his illogical argument.

There are, in fact, some logical arguments that one can use to interpret the facts. One is given by the neoclassical interpretation in the first diagram above. Expectations are depressed because the investment climate is poor (feel free to make a list of reasons for why this is the case). The demand for investment is low. Low investment demand is keeping the real interest rate low. The Fed is just delivering what the market "wants" in present circumstances. Raising the interest rate in the present climate would be counterproductive.

There is another argument one could make. Suppose that the investment climate is not depressed. There are loads of positive NPV projects out there just waiting to be financed. Unfortunately, financial conditions are such that many firms find it difficult to find low-cost financing to fund potentially profitable investment projects. In the wake of the financial crisis, creditors still do not fully trust debtors to make good on their promises. As well, regulatory reforms like the Dodd-Frank Act may make it more difficult to supply credit to worthy ventures. In the lingo used by macroeconomists, firms may be debt-constrained. The situation here is depicted in the following diagram.

The debt-constraints that afflict the business sector's investment plans caps the total amount of investment that will be financed by creditors--the investment demand schedule effectively becomes flat at this capped amount. The financial crisis moved the economy from point A to B. As before, lower investment ultimately reduces the productive capacity of the economy, so that income declines. The decline in income shifts the saving schedule down--the economy moves from B to C. The equilibrium interest rate is low--not because of Fed policy, but because investment is constrained. Savers would love to extend more credit if investors could be trusted and if regulatory hurdles were removed. But alas, present circumstances do not permit this saving flow to be released (except, potentially, to finance government expenditures or tax cuts). The effect of a policy-induced increase in the interest rate in this case would be to lower income even further. (The saving schedule would have to shift down even further to ensure that S=I.)

If the analysis above is correct, then the recommendation to increase interest rates in the present climate is off base. Low interest rates are not the cause of our ills--they are symptomatic of deeper problems. The way to get interest rates higher is to adopt policies that would stimulate investment demand (the neoclassical view) and/or adopt measures that would remove financial market frictions (the debt-constraint view). A deficit-financed tax cut (or subsidy) on investment spending would constitute one such measure.

There are, of course, other models that one could use to justify a policy-induced increase in the interest rate in present circumstances. Some members of the FOMC, for example, view the economy as having largely recovered and are now worried about the effect of very low interest rates on the prospect of future inflation. These types of arguments, however, are quite a bit different from the Gross hypothesis. But if he wants higher interest rates, maybe he should use them! A bit of a warning though: I don't think his bond portfolio is going to like the consequences.